Five Essays and a Book

Introduction

Ruskin in 1878–by Sir Hubert von Herkomer (National Portrait Gallery, London)

The Problem

John Ruskin has not been served well by his biographers. Not because—excepting perhaps a case or two—any of these authors have held a grudge of some sort against the genius whose story they had decided to tell, but, rather, because, to a one, they were the unknowing victims of a conspiracy, a concerted effort to suppress most of the evidence that, had it been widely known, would have brought to unflattering light some of the most significant emotional and psychological issues in their subject’s life, an exposing which the conspirators were convinced would damage his reputation as a great genius and, in all likelihood, their financial interests.

The decision to expurgate was made by the executors of Ruskin’s literary estate, each of whom he had appointed before his death in January, 1900. Shortly after his disappearance–a death which would be mourned by all England and much of the world–two of these executors, his caretaker cousin, Joan Severn, and his former student and long-time friend, Alexander Wedderburn, decided that, as a tribute to his genius and, hardly incidentally, as a way to make some substantial money, they would edit the entirety of his massive written output into an equally massive collection to be called The Library Edition of the Works of John Ruskin (in the end, the edition would stretch to 39 volumes, most of which were 500 or more pages in length).

However, if the Library Edition was to generate a sufficient number of subscriptions to pay for and, hopefully, exceed by some distance the cost of its creation, it would be, they thought, much less likely to do so if certain events and interests in Ruskin’s life were accorded much space. Since the executors had access not only to the majority of his original manuscripts but to thousands of unpublished letters he left behind, it would be easy to censor or destroy many of these latter, an undertaking which would make it possible to generate their own palatable version of his days.

So well-executed was the process of expurgation and fabrication they invented, all of those who would write about Ruskin’s life subsequently, using as the basis of their own works the distorted portrait of him presented in the Library Edition, and convinced that they had, in various repositories in England, access to, if not all, to at least to the most important of the documents evidencing his life, wrote biographies that underscored and even strengthened the Library Edition’s carefully purged version.

Making matters considerably worse was the fact that such writers, although they were convinced otherwise, had access to only about half of the original documents that were needed to tell Ruskin’s story fully and accurately. The remainder were housed in museums and libraries in the United States, having arrived there as a result of one of the strangest twists of literary fate imaginable. To wit:

When Ruskin’s cousin, Joan Ruskin Severn, still living in his former home, Brantwood in the lovely English Lake District, died in 1924, the immense collection of his manuscripts and letters still preserved there passed into the hands of her husband, the painter, Arthur Severn. As the 1920s neared their end, Severn, ever in need of cash, and never a particular fan of his wife’s famous relative, decided to sell all that remained of Brantwood’s Ruskiniana to the highest bidders. Despite the fact that it had been nearly thirty years since his passing, Ruskin’s reputation as one of the great literary geniuses of the nineteenth century had endured, remaining as strong in America as in Britain. The consequence was that, as the sales of Brantwood’s rarities transpired in 1930 and 1931, dozens of his original manuscripts and thousands of his unpublished letters were bought by institutions in the United States, (most prominent among these, The Pierpont Library and Museum in New York and the Beinecke Library at Yale University). Although no one fully grasped it at the time, among the letter collections that made their way across the Atlantic were the majority of the missives which would be needed to correct the false impression of Ruskin’s life embedded in the Library Edition.

The combined effects of the conspiracy and the Brantwood sales was to make it impossible to generate an accurate portrait of Ruskin’s life unless a biographer took the time required to study both “halves” of the critical materials. But none of Ruskin’s subsequent biographers—all of whom (excepting one) did their work primarily in the UK—did. The result was the creation of a “Myth of Ruskin,” a telling of his life story that accepted as more or less axiomatic the following premises: that his life with his parents had been essentially harmonious, and that, if difficulties had occasionally arisen between them, they must have been a manifestation of his unstable temperament, a not uncommon trait in geniuses; that the attacks of mental illness which would scar his last quarter century were all but surely congenital in origin; that, as a consequence of this instability, allowing an exception or two, all his works after 1870 had been tainted by his imbalances and, as a result, were and, hence, much less worthy of interest; that the failure of his ill-fated marriage to Effie Gray in the early 1850s was a consequence of a serious sexual neurosis; that his decades-long love of the much younger Rose La Touche was (to put the best face on it) obsessional; and, most damagingly of all, that his pronounced attraction to young girls was fundamentally pedophilic.

None of this is true.

Notwithstanding, the collective effect of this “Myth of Ruskin,” especially after the unflattering impressions of him nested in it had been latched onto by writers in the popular press, was, on the one hand, to destroy his once towering reputation as one of the signal intellects in the history of Western Civilization, and, on the other, to transform what “remained” of that reputation into a caricature of an old-fashioned, politically incorrect, mentally unbalanced, dead white man whose only remaining interest in the modern era was to serve as a symbol of a woefully unsophisticated age and of someone who could be held up as a representative of one of the most heinous forms of sexual behavior known.

•

The intent of the five essays and book described in, and accessible from, this Page is threefold. First, to demonstrate beyond any shadow of doubt that the “Myth of Ruskin” outlined above is just that: a myth that has had most untoward and unjust consequences on Ruskin’s reputation, both personal and literary; second, to substitute in place of this myth an alternative, considerably more accurate, and sympathetic view of the life John Ruskin actually lived; and, third, to underscore the truth of the assessment, accepted by thousands during his own time, that Ruskin was a genius of the first order, one whose works, once we determine to accord them the consideration they deserve, will quickly be shown to possess a series of beacons which are eminently capable of helping us light our way through the numerous dark turnings and cul-de-sacs of our own troubled era.

How These Works Came to be Written

Long-time followers of Why Ruskin will be aware that, over the course of its half decade of existence, little space has been allotted to discussion of Ruskin’s life. The principal reason for this has been, remains, and will remain, my conviction that what is most important about Ruskin is not the story of his life, interesting as that may be, but his relevance as someone whose wisdom, like Plato’s or Dante’s, remains remarkably useful in our contemporary world.

A second reason for this omission, however, has been my lack of willingness to give space over to discussions of the “Myth of Ruskin” above outlined, if only because considerable experience demonstrates that, much more often than not, whenever that myth enters a room where Ruskin is being discussed, the intruder, not unlike the huge and vile dragons always hovering overhead in “The Lord of the Rings” films, descends, co-opts the discourse, a usurpation which immediately causes the personage known as Ruskin the Literary Genius and his excellent relative, Ruskin the Great Humanitarian, to disappear.

Now, however, I believe we have all the means necessary for, if not banishing altogether, then at least markedly weakening the seductive power of the mythical intruder. In which light, I have decided to make available on WhyRuskin, some materials for your perusal. The following paragraphs provide an overview of how these works came to be written.

A quarter of a century ago, still new to my Ruskin work, I had the good fortune to visit, at his home in Cortland, New York, Professor Van Akin Burd, arguably the greatest Ruskin scholar of the last century. In response to a telephone question of mine asking whether he knew of any link between Ruskin’s work and Plato’s (I knew Plato well and, now reading Ruskin intently, I strongly suspected such a connection). Why didn’t I come to Cortland and we’d talk further about it? When I arrived at the house on Forrest Avenue, however, he informed me that, although he’d looked through most of his Ruskin material, Van (he immediately said I should call him that) told me he couldn’t answer my question. However, he immediately said that, if anyone could, it would be Helen Viljoen (pronounced, “Fil-yoon”), a Ruskin biographer who, by that time, had been dead for over twenty years. Viljoen was, Van said, despite the fact that she never published much during her lifetime, by far the greatest of all of Ruskin’s biographers. For decades, she had amassed mountains of new material on his life, material never consulted by other biographers, intending it for use in a magisterial new “life of Ruskin.” Unfortunately, in 1974, with her biography still very much unfinished, multiple sclerosis, a disease that had been worsening for years, cut her life short. Because we were good friends, Burd went on, and given that both of us had dedicated our lives to telling Ruskin’s story truthfully, she left her massive collection of Ruskiniana to me!

But, as he studied the contents of Viljoen’s huge gift, Burd continued, he quickly saw that, given his age (then nearing seventy), he would never be able to complete, as Viljoen had hoped, her revolutionary new story of Ruskin’s days. And so, knowing how valuable for scholars her legacy was, he donated the entirety of her collection in The Pierpont Library and Museum in New York where she had research on Ruskin for decades. Viljoen, he said as he concluded, had known more about Ruskin than any human being ever had. And so, if anyone would know of a Plato-Ruskin connection, it would be her. Why didn’t we two go to the Morgan, call up the boxes containing her biographic work and, as I went through them, I would be able to learn the answer for myself? And so, not much after, we went.

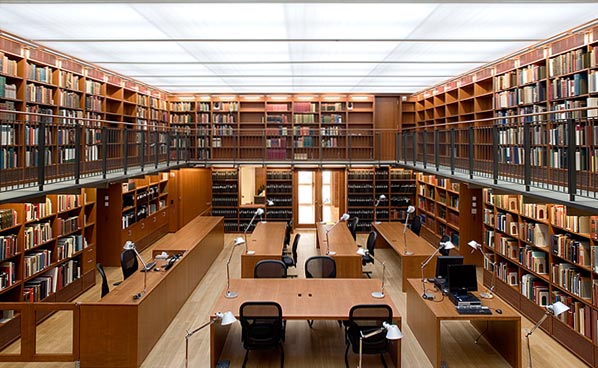

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

The Scholars’ Reading Room, Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

But, I quickly learned, as I began my search through Viljoen’s massive legacy, that finding that answer was nowhere near as easy as I imagined it would be. There was so much! How could I possibly find what I was interested in in just a few days? It was then that I came across a typescript that Viljoen had composed not long before her death. “My Outline of Chapters” was a summary, intended for later scholars, of the new arguments about Ruskin’s life she had planned to make had her biography been published. I was not more than a few pages into it when I knew that Van had been right to use the word “revolutionary” as a descriptor. For in her brief typescript, Viljoen told of her shock, when she visited Ruskin’s home, Brantwood, in 1929, when she had learned of the conspiracy to censor his story, a discovery that been so powerful that she had decided on the spot to become the first person to tell Ruskin’s story rightly. In the remainder of her pages she outlined much more of what she would have said in what she thought would likely become, in the end, fifty chapters.

It wasn’t the estimated size of her work that amazed me, it was that her biography was going to be laden with revelations about Ruskin’s life, revelations about which other biographers had no, or, at the most, modest, awareness! On our return trip to Upstate New York, I told Van what I had learned and asked him if anyone else knew what was contained in Helen’s boxes at the Morgan. No one, he replied, adding that it might be good if someone did make known all the new things she had found out about Ruskin.

The result was that, completely unexpectedly (such is life!), I began to work—for over two decades as it turned out!—on a series of essays (and, in time, a book) about Helen Viljoen and her “life of Ruskin.” These essays—there are five—and the book are summarized below.

in 2019, the year of the bicentenary of Ruskin’s birth, the last two essays–“Ruskin’s Sexuality” and “Ruskin—The Forgotten Legacy in America”—were published on The Victorian Web. Shortly after that the thought occurred to me that I now had, considering the five essays and book together, enough radically new material on Ruskin’s life–each of which had initially been published in different years in different journals or websites–that might, if it was made accessible in one (cyber) place, prove useful to those who, whether they were scholars or not, were interested in Ruskin, a locating which would allow them as they made their way through this alternative material to make their own judgments about how Ruskin had lived his days. Hence, the decision to make these materials available on WhyRuskin.

In the time that has passed since taking this decision, I have substantially updated the first three of the biographic essays–“John Ruskin’s Dark Star,” “Ruskin in Milan,” and “Ruskin’s Dark Night of the Soul”–revising (slightly) their original arguments, adding a number of photographs, and, most importantly, interpolating substantial amounts of new biographic material on Ruskin which was unavailable when these works were first published. (For which reason, the iterations of the essays here should be seen as their “definitive” versions.)

The five essays are introduced in the order in which they were first published. While each can stand on its own, to get the complete picture of the alternative story of Ruskin’s life I am advancing, it would be best if they were read in that sequence. (Inevitably, given that each essay was written as a “stand-alone piece,” there is some repetition of arguments.)

For all of these works, I’ve given titles, information indicating their original places of publication, and a summary of the principal arguments to be found in each. For the first thee essays I have included, following a summary, a link to a PDF version of the whole essay. For easier reading, these can be downloaded and shared. The last two essays can be read via links to their location on The Victorian Web. Finally, after providing a brief outline of the book (now out-of-print), I’ve included a note telling how to get a copy of it.

Finally, I will be more than happy to discuss any questions that might arise concerning any aspect of Ruskin’s life that is stimulated by what you read. I hasten to add, however, that such discussions will not take place within the context of the regular posts of “Why Ruskin,” the intent of which will continue to be the providing of instances which make Ruskin’s brilliance palpable as well as demonstrating why his work still has great relevance to we moderns. Just send an email to me at jimspates43@gmail.com.

The works are (the numbers correspond to the order of their presentation):

The Essays

1: “John Ruskin’s Dark Star”

2: “Ruskin in Milan” (co-authored with Van Akin Burd)

3: “Ruskin’s Dark Night of the Soul”

4: “Ruskin’s Sexuality”

5: “Ruskin–The Forgotten Legacy in America”

Book

6: The Imperfect Round: Helen Gill Viljoen’s ‘Life of Ruskin’

All have been written to honor the pioneering work on Ruskin’s life done by Professors Helen Gill Viljoen and Van Akin Burd.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

The Essays

1

“John Ruskin’s Dark Star: New Lights on his Life based on the Unpublished Biographic Materials and Research of Helen Gill Viljoen”

Original Publication: Bulletin of the John Rylands Library

University of Manchester, Vol. 82 (2000): 135-91.

Updated: 2020

Helen Gill Viljoen studying her Ruskin manuscripts in her New York apartment, 1960s

Summary: Early in 1929, a young American scholar, Helen Gill Viljoen, arrived at Ruskin’s former home, Brantwood, in the English Lake District, hoping to discover there the sources he had used to inspire his acclaimed Modern Painters books. To her surprise, she found that, even though Ruskin had died in 1900, the house still contained thousands of Ruskin’s letters—the great majority of which remained unpublished—most of his diaries, and many of his famous manuscripts. Having been given permission, she started reading the letters, quickly discovering–to her dismay–that, as a whole, they painted a very different picture of Ruskin than the sanguine image which had been set out in the biographic chapters of the supposedly definitive, 39-volume Library Edition of the Works of John Ruskin which had been published between 1903 and 1912. The Ruskin who lived in these letters, she saw, had been a deeply troubled man in serious conflict, all his life, with his controlling, self-centered parents. This conflict, which she would come to call “the ruinous struggle” was so severe it crippled him emotionally and significantly compromised his brilliant work. Reading further, she learned that other critical aspects of his personal life had been downplayed in the Library Edition, almost, in some cases, to the point of being complete suppression. In other words, an orchestrated cover-up had been perpetrated so that those who had been involved in the creation of the Library Edition could tell a manufactured story of Ruskin’s life–a fact which meant, in its turn, that a biography of Ruskin as he had really lived did not exist.

Almost immediately, Viljoen’s interest in writing a book on Modern Painters evaporated (such is life!), as she decided that she would be the one to write Ruskin’s story truly. And so, for the next 45 years, living and working in New York City, Viljoen dedicated herself to ferreting out every scrap of information about Ruskin’s life that had ever—and, even more importantly, never—seen the light of day. During these same decades, she became the recipient of other major, previously unpublished, caches of revealing biographic material on Ruskin, material no one else had any idea existed. All of it, she found as she examined it, enriched the Ruskin story she wanted to tell beyond her wildest dreams. In the end, she was never to complete her great work, partly because she had become overwhelmed by all she had collected, and, finally, because an incurable, always-worsening and weakening illness (multiple sclerosis) would bring her to a premature death in 1974.

This essay recounts the story just summarized in detail and outlines the principal new insights (and some of the most important evidence for these) about Ruskin’s life Viljoen would have made. As it does so, it underscores the view of the late Van Akin Burd, that, had Viljoen ever published, hers would have become the definitive Ruskin biography. Concluding, it assesses what the unfortunate consequences for Ruskin biography have been for not having had Viljoen’s research and data in hand as biographic work on Ruskin has continued, and argues that the inclusion of such are critical for creating accurate accounts of Ruskin’s life in the future.

To read the essay, click here: John Ruskin’s Dark Star

__________________________________________________________________________________________

2

“Ruskin in Milan, 1862: A Chapter from ‘Dark Star,’

Helen Gill Viljoen’s Unpublished Biography,”

co-authored with Van Akin Burd

Original Publication: The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies,

Vol. 13 (New Series), Fall, 2004: 17-61.

Updated: 2020

Van Akin Burd and Jim Spates on the Occasion of Van’s 100th Birthday Celebration, April 19, 2013, Cortland, New York

Summary: Between the early 1930s and late 1940s, Helen Gill Viljoen composed over thirty draft chapters for her Ruskin biography. Between 1948 and 1960, however, her discoveries of major new caches of Ruskiniana dictated that many of these drafts would require rewriting if the story of his life was to reflect everything she now knew to be of relevance. The immensity of the task plus the ever-worsening effects of multiple sclerosis ensured that this revising never occurred. Nevertheless, study of the drafts of her chapters made it clear some were essentially complete as they stood. Her “Milan” chapter, rendered here in its entirety, is one such. Reporting primarily on Ruskin’s trip to Milan in 1862, it serves, simultaneously, as an example of Viljoen’s considerable editorial skill and as a remarkably well-documented presentation of the most revisionist theme of her biography, her argument that the presence and destructive effects of what she called Ruskin’s “ruinous struggle” with his parents, Margaret and (particularly) John James Ruskin, was a familial cauldron that bore the lion’s share of the responsibility for crippling him emotionally and, eventually, for derailing his genius.

An “Introduction” by the late Van Akin Burd tells the story of his long friendship with Viljoen and makes his abiding admiration for the inestimable quality of her work tangible. Following this, her “Milan” chapter is presented in its entirety with, as necessary, notes by myself linking some of its dominant themes to their place within the context of Viljoen’s biography as a whole. The “Afterword,” written by myself, situates “Milan” within the context of her overarching biographic design and, citing additional materials from her other draft chapters and unpublished manuscripts, shows how she had planned to demonstrate, in the last third of her biography (which would never be written), how the adverse effects of the ruinous struggle would continue to disfigure Ruskin’s days until his end arrived on the 8th of January, 1900. The necessity for future Ruskin biographers being thoroughly familiar with Viljoen’s theses and the thousands of draft pages she wrote is emphasized. A “Coda” [not included in the first published version of this essay], using two pages from Viljoen’s copy of Ruskin’s Diaries as these are currently published, demonstrates, simultaneously, the assiduous nature of her research technique, the striking depth of her understanding of Ruskin’s life, and makes it clear that, because of that depth of knowledge, she understood things about her subject’s days that had never occurred to any other biographer.

To read the essay, click here: Ruskin in Milan

____________________________________________________________________________________________

3

Ruskin’s Dark Night of the Soul:

A Reconsideration of his Mental Illness and the Importance of Accurate Diagnosis for Interpreting his Life Story

Original Publication: The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies,

Vol. 18 (New Series), Spring 2009: 18-58.

Updated: 2020

Ruskin, Self-Portrait, 1874

Summary: One of the most frequent topics that rises to the surface when discussing Ruskin is the role that mental illness played in his life and work. Although a considerable amount of evidence demonstrates that he was often and deeply depressed early in his adult life, his first debilitating attack of what was (then) called “brain fever”–which included a period of psychosis–occurred in 1878 when he was 59. Similar attacks would occur at roughly two-year intervals over the course of the next decade until the moment arrived in late 1889 when he left the public stage to live in seclusion at Brantwood until his death in early 1900.

Prior to the research presented in this essay, all views of Ruskin’s illness and its consequences have been speculative, voiced by non-specialists about diseases most knew little to nothing about. In this study, I undertake a systematic analysis of Ruskin’s mental disturbances, my goals being to find out what his illness actually was and, that accomplished, to analyze its effects on his life and work. I begin by consulting The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the definitive volume used by professional psychiatrists for such diagnoses. Using a significant number of (mostly) unpublished letters—many of which are preserved in American institutions and, for that reason, unknown to Ruskin’s UK biographers—it soon became clear that he did not display the characteristics linked to Bipolar Disease (Manic Depression), the affliction most commonly conjectured; nor did he possess the traits of other suggested mental imbalances (e.g., schizophrenia). However, he did exhibit, in abundance, the unhappy traits that always attend an illness known as “Major Depression with Psychotic Features.”

After providing considerable evidence demonstrating the presence of this illness, it became possible to reject the supposition (always offered without convincing evidence) that Ruskin’s imbalances were congenital, the product of a biologic time-bomb which had been long waiting to go off, and substitute for that guess an explanation that simultaneously accounted for his early bouts of depression and the extremely serious attacks of later years. By presenting abundant holographic and published evidence missed by other writers, I argue that Ruskin’s disturbances were the result of the cumulative effects of a series of traumatic life experiences, principal among these being his abiding conviction that he had failed miserably, and repeatedly, in his attempts to transform the world into a better place, the nearly unbearable sorrow occasioned by the death of the love of his life, Rose La Touche, and the always lingering, always lacerating, effects of what Helen Viljoen had called his “ruinous struggle” with his adoring but domineering parents, Margaret and John James Ruskin, a struggle which continued internally long after their deaths. At the essay’s end, I assess the radical implications of these findings have for subsequent Ruskin biography.

Note: While each of the two essays summarized above–“John Ruskin’s ‘Dark Star’,” and “Ruskin in Milan”–have an appreciable amount of new material in them, this final version of “Dark Night” has considerably more, largely because much of this material, especially that taken from Ruskin’s letters to and from the American ex-repatriates, Francesca and Lucia Alexander, during the 1880s–essential for their ability to throw new light on his mental health (or, more often, the lack of it)–could not be incorporated in the originally published version of this essay because of limitations of space. (No other Ruskin biographer appears to have been aware of the Alexander collection.)

To read the essay, click here: Ruskin’s Dark Night of the Soul

____________________________________________________________________________________________

4

Ruskin’s Sexuality:

Correcting Decades of Misperception and Mislabeling

Original Publication: Since January 2019, on The Victorian Web (see link below)

Ruskin, Self-Portrait, 1862

(Ruskin Library, Lancaster University)

Summary: By leagues, the most damaging charge against Ruskin’s character has been the claim, first made by a relatively recent biographer, that he was a pedophile. The allegation—set forth without providing a scientific definition of the illness and supported by little evidence—was soon picked up by the popular press (and some scholars) on both sides of the Atlantic, with the result that, in short order, Ruskin’s already drooping reputation descended into the nethermost regions of public opinion. The intent of the present study was to discover whether the above assertion and a related other—that, throughout his adult life, Ruskin was sexually interested in young girls and women—were true and then, depending on the answer, assess the implications for properly interpreting his life story and future research on same.

To begin, as was the case in my study of his mental illness (“Ruskin’s Dark Night of the Soul,” summarized above), I turned to The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illness to determine if the available evidence (much of it drawn from collections of Ruskiniana in America and, as a result, never deeply evaluated by those writing on his life in the UK) supported such unhappy characterizations. It was found that he possessed none of the criteria associated with pedophilia or for any of the fixations some men exhibit for children or young girls. This determined, I then asked how it had come to pass that Ruskin, who over the course of much of his life, had been regarded as a sage of epic stature, had been unjustly singled out as the bearer of such heinous traits?

To provide the answer, I first detailed the systematic—and unfortunately most successful—attempts made by the executors of Ruskin’s literary estate to censor aspects of his story that, had these been generally known, the executors of his literary estate believed, would have damaged his reputation and very likely dissuaded many from subscribing to the expensive 39 volume edition of Ruskin’s complete works they were publishing. Among the interests the executors chose for suppression were: (a) despite the fact that he was always open concerning it (hundreds of letters attest), letters expressing his enduring love for the much younger Rose La Touche (a love that endured for Ruskin long after Rose’s death); (b) nothing indicating his (completely chaste) interest in young girls; (c) any mention that there once existed (in the 1880s) a possible romantic link between him and an artist he sponsored (Kate Greenaway); (d) and every scrap of evidence that he once had great hope of marrying a young woman (Kathleen Olander) whom he had met in London in the late 1880s.

Censorship, however, always being the insurer of its own demise, in due course, some of this suppressed evidence started to surface, only to be interpreted by some biographers and many others writing in the popular press, as proof positive that something sexually odious had being going on with this once thought-to-be-pristine Ruskin fellow. But, like those who, without any expertise, had too glibly claimed that he had one mental illness or another, those who castigated him for his alleged erotic misbehaviors had no medical understanding of the sicknesses they claimed he had. Their readers, having none of this knowledge either, took what was said at face value, and, as a result, enormous damage was visited on Ruskin’s reputation.

In subsequent sections of the essay, I show why it is that society as a whole is always in need of someone who can be used as a symbol of behaviors collectively forbidden. In the present sexually obsessed era, Ruskin became a perfect choice for such singling out, however flimsy was the evidence for the indiscretions he was accused of. The upshot was that, over the course of the past few decades, “Ruskin!” has become, and, unfortunately, to some extent, still remains, a social and moral pariah, an easy emblem of the severely sexually neurotic and despicably perverse. In a late section, I show, by means of an analysis of his deep friendships with some adult women, that the exact opposite of what was so facilely claimed, was what was actually happening: Ruskin having no erotic designs whatsoever for such women, did all he could to keep them at arm’s length so he might go on with his society-saving work without distraction.

In the last chapter, the injustice of the accusations of sexual perfidy now made clear and an explanation of the reasons of why it had come to the fore explained, I reprise the argument—made some decades ago by Sir Kenneth Clark—that Ruskin remains, now as when he lived, as one of the greatest and most humane geniuses in the history of Western Civilization. I end by arguing that a thorough reconsideration of his work would be something from which we can still greatly profit.

To read the essay on The Victorian Web, click here: Ruskin’s Sexuality

____________________________________________________________________________________________

5

Ruskin—The Forgotten Legacy in America

Original Publication: Victorian Visionary: John Ruskin

and the Realization of the Ideal, eds., Peter X. Accardo and R. Dyke Benjamin

Cambridge, MA: Houghton Library/ Harvard University Press: 37-50.

Since May 2019, on The Victorian Web (see link below)

Francesca Alexander, from a letter to her “Fratello,” John Ruskin, mid-1880s (Boston Public Library)

Summary: For an accurate rendering of the story of Ruskin’s life, the discoveries made by Helen Viljoen during her visit to Brantwood in 1929 remain momentous, even though their full significance has yet to be appreciated. Unexpectedly, while at Brantwood in the early months of that year, Viljoen learned that, in order that they might tell Ruskin’s story in a way that would be palatable to the general public and especially to those who might invest in the Library Edition of Ruskin’s works they were preparing for publication, the executors of his literary estate bowdlerized the story of his life. Immediately, now aware that an accurate rendition did not exist, Viljoen determined that she would become Ruskin’s first true biographer, someone who would compose a considerably more complete and more humane story of his days. Returning to America, she set to work. As it happened, and as explained in detail in the first two essays of this series–“John Ruskin’s ‘Dark Star’,” and “Ruskin in Milan”–she would never complete that biography.

In this final essay, after briefly rehearsing the decision made by Ruskin’s executors to expurgate his life story and explaining how it happened that vast amounts of his most revelatory letters came to be preserved in America, I show how the limited amount of biographic work Viljoen did publish and the more substantial works published by Van Akin Burd were beacons for later Ruskin biographers, beacons which, had their lights been followed, would have led other biographers to the major caches of Ruskiniana preserved in the United States, and, by so doing, all but surely would have prevented much of what subsequently happened to denigrate Ruskin’s reputation over the course of the past few decades.

But Viljoen’s and Burd’s beacons were, for the most part, overlooked. It is the goal of this essay to serve as a guide for future Ruskin researchers, a guide that will bring them to the American institutions which, collectively, contain the information needed to tell the whole of Ruskin’s story.

Most prominent among these institutions are the Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum in New York and the Beinecke Library at Yale University (the critical importance and extent of the relevant holdings of each cannot be overemphasized). But other locations will also benefit studious eyes: The Huntington Library near Los Angeles (Ruskin’s letters to his very dear friend, Susie Beever), The Boston Public Library (the critical exchanges between Ruskin, Francesca, and Lucia Alexander–see, above, “Ruskin’s Dark Night of the Soul”), The Houghton Library at Harvard [C. E. Norton’s Ruskin letters and, as significantly, his exchanges with Joan Severn after Ruskin’s death when the conspiracy to suppress was afoot (Norton was another of Ruskin’s dear friends and the third named executor of his literary estate)], The New York Public Library (various smaller but important letter collection), Columbia University (Ruskin’s letter exchanges with his publisher, George Allen—hundreds!), The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (the sorrow-laden letters Ruskin sent to Joan Severn in 1888 during his last trip to the Continent), and The Ransom Library at the University of Texas at Austin (his correspondence with his former student and one of the editors of the Library Edition, Alexander Wedderburn). There are other collections of lesser, but hardly irrelevant, import (all noted in more detail in this essay). To put it directly, only when these collections on the western side of the Atlantic have been examined with care and their contents synthesized with the most important Ruskiniana available in the UK will it become possible to write, for the first time, Helen Viljoen’s never gained dream, a definitive biography of John Ruskin.

To read the essay on The Victorian Web, click here: Ruskin–The Forgotten Legacy in America

__________________________________________________________________________________________

A Book

6

The Imperfect Round: Helen Gill Viljoen’s

“Life of Ruskin”

(Geneva, New York: Long View Press, 2005)

Summary: Some years ago, The Ruskin Society of London asked if I would write—for “the record” and future Ruskin scholars—a detailed account of Helen Viljoen’s momentous visit to Brantwood in 1929 and her subsequent “life of Ruskin.” The Society said it would gladly cover the costs of such an effort. The result was the book, the cover of which is shown above. Much that is in it is not available elsewhere. Briefly, its contents are:

Part One, “Oh, Bill, What Food I Have for a Totally New and Revolutionary Biography!” tells, in five chapters, the story of Viljoen’s visit to Brantwood in 1929. Largely based on letters she posted almost daily (sometimes twice a day!) to her husband, Bill Viljoen, in America, they all but overflow with her mounting enthusiasm as she makes her way through the thousands of Ruskin’s unpublished letters at Brantwood which, considered collectively, demonstrated beyond doubt that the story of his life as that had been told in the Library Edition of his works was a calculated and systematic bowdlerization. That insight made it clear that an accurate Ruskin biography yet to be written, and then to Viljoen’s decision that she would be the one who would write it. Also included here is Viljoen’s unpublished essay, “Mr. Collingwood on Ruskin,” a memoir of her many conversations with Ruskin’s former student, secretary, and devoted friend—who lived near Brantwood—taken from notes made during her Brantwood days.

Part Two, “My Waggon to a Star,” starts a little more than three decades later, in 1960. The opening chapter presents Viljoen’s previously unpublished lecture, “The Scholar and His Life,” her attempt to summarize the immense amount of work she has done on her still incomplete biography during the years that have elapsed since her discovery days at Brantwood. The following four chapters, based primarily on letters to and from a wide spectrum of her correspondents, are set in her apartment at 167-10 Crocheron Avenue in Queens, New York, the place where virtually all her Ruskin work (when she was not reading and transcribing in various libraries) was done. The chapters detail her later discoveries of major caches of previously unavailable biographic materials: Ruskin’s adolescent sermons on the Pentateuch, the Bowerswell Papers, the writing of Ruskin’s Scottish Heritage (the only volume of her biography ever published), the F. J. Sharp Collection, and her realization that, throughout most of his authorial life, Ruskin embedded within his works autobiographic allegories symbolically exposing the truths of the various tragedies that hindered him from accomplishing all that he once wished he could.

167-10 Crocheron Avenue, Queens, New York, where Viljoen

lived for more than four decades

Part Three, “Where’s John?” The three chapters cover, in the first pair, the period from 1960 until Viljoen’s death in 1974, a time during which she had to face the fact that her four and a half decades old dream of writing the definitive Ruskin biography would remain just that, a dream. Even publication of her superb The Brantwood Diary of John Ruskin in 1971, and the subsequent praise accorded it, could not save her from that soul-crushing realization. Taken as a whole, these last years were a sad, ever more deteriorating time. The third chapter relates the story of the discovery, in 2001, by Van Akin Burd and myself of her unmarked grave in her family plot in Beechwoods Cemetery in New Rochelle, New York, a site not far from the house where she had grown up.

Part Four, “Recollections” brings the tale of Viljoen’s “life of Ruskin” to its close, offering, in two chapters, first, my analysis of how it came to be that—beyond the obvious barriers that kept her from completing her great work (her discovery of more material than she could handle; her incurable illness)—this extremely intelligent, talented, and unimpeachably knowledgeable biographer kept taking on new work and projects (some of which had little of importance to add to the Ruskin story she intended to tell) that diverted her from a much needed redrafting of some early chapters of her biography and the writing of her last ones. The answer lay—as it had for Ruskin, as it does for many of us—in traumata she had suffered in childhood, traumata which continued to unhinge her adulthood, traumata which, because she could not see them clearly, dissuaded her from completing her great project

“All noble things,” Melville wrote in the sixteenth chapter of Moby Dick, “are touched with melancholy.” So it proved to be the case with Ruskin, and so it proved to be the case with Helen Viljoen, her prodigious work on her hero’s life being left, at the moment of her death, in significant disrepair. Even after she had become fully aware that she would never live to tell her story of Ruskin, Viljoen never relinquished her admiration for the great Victorian to whom she had devoted her life almost a half century before, telling her good friend in England, Janet Gnosspelius, in a late letter, “Within my own heart, I still retain my innermost respect for Ruskin…[retain my] faith in his ultimately abiding significance as the Human Being Bespoken…”

The book ends with an Epilogue, and an Appendix, this latter summarizing for scholars the essential contents of “The Helen Gill Viljoen Papers” at the Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum in Manhattan.

Now out-of-print, I would be glad to send you a copy of the book if you contact me at jimspates43@gmail.com.

____________________________________________________________________________________________