‘Tis the season!

To be jolly, yes. But also, of course, to buy, accumulate, raise ever higher our own particular, often peculiar, mountain of possessions, possessions almost always past the point of need, almost always ensconced in the realm of the indulgent or whimsical.

It seems odd, this perpetual passion for possessions, don’t you think, when we look at it with any detachment? What possible use could all these things have when we have, as most of us reading this web page have, enough; enough food, enough clothing, enough shelter, with a little something left over for a special love or avocation or special relaxation?

Things clarify when we step back a bit further. For, from this more abstract distance, we can see that, almost to a person, we are in thrall to a powerful cultural vision of what signals to ourselves and others that we have lived (are living) a meaningful life.

Here is Ruskin’s description of that vision, extracted from his most excoriating lecture, “Traffic”–for more on which, see: Post 57 –which he delivered to the rich and powerful of Bradford in 1864:

Your ideal of human life then is, I think, that it should be passed in a pleasant undulating world, with iron and coal everywhere underneath it. On each pleasant bank of this world is to be a beautiful mansion, with two wings, and stables, and coach-houses; a moderately-sized park; a large garden and hot-houses; and pleasant carriage drives through the shrubberies. In this mansion are to live the favored votaries of the Goddess [of Getting-on]: the English gentleman, with his gracious wife, and his beautiful family, always able to have the boudoir and the jewels for the wife, and the beautiful ball dresses for the daughters, and [hunting grounds] for the sons, and a [special place for] shooting in the Highlands for himself.

At the bottom of the bank, is to be the mill; not less than a quarter of a mile long, with a steam engine at each end, and two in the middle, and a chimney three hundred feet high. In this mill are to be in constant employment from eight hundred to a thousand workers who never drink, never strike, always go to church on Sunday, and always express themselves in respectful language.

Is not that, broadly, and in the main features, the kind of thing you propose to yourselves?

British, European, American, indeed World, Dream this: a unique idea of “living well” that has been deeply embedded in us all: Life is good, we have been taught, when, and only when, all its accouterments can be bought, enjoyed, and, after our transitory interest in most of them disappears, rebought in a slightly varied guise.

Although it sounds lovely, it is anything but a free Dream. It is a Dream which demands that we accumulate rather remarkable amounts of money to make its actualization possible, a Dream which forces us into the intense competition that securing such a large cache of money will require. It is also a Dream which intentionally overlooks, or hides, the unhappy consequences of its actualization, as Ruskin made palpable in the sentences which immediately followed the excerpt above:

It is [a vision, he wrote, that is] very pretty indeed, seen from above. Not at all so pretty, seen from below. For, observe, while to one family this [elegant existence] is indeed the Goddess of Getting-on, to a thousand families, she is the Goddess of not Getting-on.”

In other words, if we get rich, somebodies, somewhere, must, by logical extension–there being only so many pennies or pence available for assembly at any given time–become poor or poorer. To paint the picture even more starkly, while we swim in the heated pool, or eat the perfectly prepared venison upstairs, others, downstairs, struggle mightily or drown in some polluted pool in streets which we never walk, streets which, should we ever be in their vicinity, we would avoid like the devil.

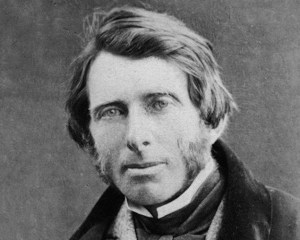

Ruskin in 1863

The son of considerable privilege, it took Ruskin some time to evolve to this understanding of how the accumulation of money (or lack of that accumulation) really worked. As we know, he grew up as the only child of a very rich sherry merchant, John James Ruskin. Throughout his first years, he wanted for nothing, was indulged (indeed, spoiled), provided with the best private tutors in literature, art, and science, taken, at his expensive wish, to Europe for long sojourns by his parents so that he might locate the places where his hero, the painter J. M. W. Turner, had set down his easel to create his glorious visions of nature, was enrolled (John James not being of sufficiently upper crusted status) as a “Gentleman Commoner” at Oxford–and much more.

He began his study of the great cathedrals of Europe in the later 1840s, and, as he learned, came to a realization that would change his life forever. He discovered that the tens of thousands who built these greatest of the world’s great edifices were not merely “workers,” but were, instead, complex and talented human beings (Post 99: “The Little Man and the Dragon”), learned further, to his horror, that the majority of these talented and unknown souls had hardly ever been paid adequately for the marvelous work they did, had been, to put it bluntly, exploited and, as a result of the short fall of remuneration, had lived lives of considerable deprivation, their life-force used, and then, the sapped remnants discarded like so much chaff from the wheat.

About which realization, he wrote his father, in a letter posted on 15 November 1853 (the original is in the Ruskin archives at Yale’s Beinecke Library): “I believe that my own religious difficulties, and most other peoples’, arise from my not obeying the plain command, ‘Take what thou hast and give to the poor’ [Matthew 19: 21]. In other words, I can’t go on buying missals and [rare and expensive] pictures if I feel that they are painted with people’s blood which, in the present state of society, they are. I will write more on this…’” (Which he did.)

Avarice, then, appears to be the problem. For me, as much as I can get. For you, as little as can be arranged. To put it directly, as he wrote in the second essay of Unto this Last (to the marked displeasure of his well-heeled contemporaries who were most desirous of keeping the discomfiting fact hidden): “the art of getting rich is the art of keeping your neighbor poor.”

But the real problem is deeper than covetousness, the real problem is inherent in the image of opulent living which sets the whole devouring system in motion. The Dream tells us to go out and gain as much for ourselves as we possibly can while the devil takes the hindmost, a Dream which is made visible by the ceaseless images that are set before us: of monumental mansions in Hollywood or Palm Beach (Presidents live there!), or of the Maseratis that are occasionally, like the mechanized horses they are, taken out of their protected garage stables for envious drives , of the diamonds which weigh down Mariah Carey’s fingers, of the climate-controlled cellars which protect and preserve the finest of fine wines.

Perhaps the most important and disturbing thing about this Dream is that it is insatiable. You can never, we say, have too much money. You can never have too many things. Your status as someone of significance is forever dependent on such surpluses. The poor entertain the Dream as intensely as the already advantaged. In the marvelous musical, “Fiddler on the Roof,” the main character, Tevy, is a poor milkman. Not long after the show’s opening, lamenting this painful lot, he sings, “If I were a rich man,” among its lyrics, are these:

I realize, of course, that it’s no shame to be poor

But it’s no great honor, either.

So what would have been so terrible if I had a small fortune?

I wouldn’t have to work hard…

Right in the middle of the town,

A fine tin roof with real wooden floors below.

There would be one long staircase just going up

And one even longer coming down,

And one more leading nowhere, just for show…

Looking like a rich man’s wife,

With a proper double chin,

Supervising meals to her heart’s delight.

And strutting like a peacock,

Oy! What a happy mood she’s in,

Screaming at the servants day and night.

They will ask me to advise them,

Like a Solomon the Wise…

And it won’t make one bit of difference

If I answer right or wrong

When you’re rich they think you really know…

As I prepared this post, the frightful story of our present, tragic opioid crisis appeared at the top of the news again. It was told that 150 people a day die from their addiction to, or from an overdose of, these treacherous drugs. The company that has been most deeply implicated in creating the crisis–as a result of its tireless efforts to convince doctors to prescribe these drugs even in the face of a growing number of reports of their fatal consequences–is Purdue Pharma. The reason for the company’s abrogation of what would, by almost everyone, be immediately viewed as an ethical imperative to stop and make atonement for the catastrophe it has manufactured, is not hard to find. Purdue’s take has been vast. Although in the last few weeks the company agreed to give $3 billion toward alleviating the worst effects of the crisis, it turns out that, during that same period, its executives were surreptitiously sequestering nearly $11 billion of the company’s reserves into their own personal accounts in tax-sheltered places like Switzerland and the Cayman Islands. The following New York Times article gives the details (click on the headline):

Sackler Family of Purdue Pharma Siphons off Billions

Immediately, once the enormity of these efforts to seclude registers, one wonders what in the world this $11 billion would be used for, what could it possibly buy which this family, its members already billionaires many times over, does not already have. But, as soon as the thought appears, the answer is achingly apparent. It is having the $11 billion that is the important, status-securing thing. Like Tevye, the point is to have one more staircase leading nowhere, just for show. That this astonishing amount of surplus money could have been used to make major reparations for those harmed by the sale of Purdu’s drugs, that it could have been (should have been) used to build hospitals, roads, bridges, colleges, homes for the homeless and indigent, and much more, never entered the sequesterer’s minds. The art of making yourself rich, envy-of-all-the-world-rich, is, quite literally, keeping your neighbor poor. Jingle all the way.

Here is Ruskin’s description of this ego-centered impulse (from another of his greatest lectures of the 1860s, “Of Kings’ Treasuries”):

We do not understand by this [insatiable drive to accumulate] the mere making of money, but the being known to have made it, not the accomplishment of any great aim, but the being seen to have accomplished it. In a word, we mean the gratification of our thirst for applause. That thirst, if the last infirmity of noble minds, is also the first infirmity of weak ones; and, on the whole, the…the greatest efforts of the race have always been traceable to the love of praise, as its greatest catastrophes to the love of pleasure. [What we who accumulate really wish is “to get] into good society..,” not that we may have it, but that we may be seen in it; and our notion of its goodness depends primarily on its conspicuousness.

Preening then, is the purpose.

Ruskin was no Pollyanna. Whenever he exposed a problem, he proposed a solution. Words were one thing, he said. But doing was quite another. While, as noted, there are many possible remedies–legal, moral, institutional–that might be set in motion to alleviate the damages done by a calamity like the opioid crisis, one action, he advised, was immediately to hand for everyone: to stop oneself from participating in the behaviors which contribute to any such misery-inducing outcomes. To take the seductive image that is the subject of this post: if the consequences to our subscription to an insatiable Dream will inevitably result in one way or another in the impairment of others, then the solution lies in cancelling our subscription to the Dream. In making such a cessation, even though one might not be able to affect redress everywhere, at least one can rest assured that one is no longer contributing to the crisis.

The cancellation is not so terribly hard to affect. It is relatively easy to estimate the amount one needs to keep yourself and those dependent on you living decently; to estimate how much is enough to pay the rent or mortgage, have adequate clothes, enough food, to ensure that something is set aside for a rainy day or old age (a trickier category this, demanding considerable self-reflection), with a bit left over for a little indulgence. Less, always, this amount than one might think before trying the exercise.

I want to end with a poem, one of my favorites. It graced a New Yorker page some years back. It was written by the satirical American novelist, Kurt Vonnegut, about his good friend, another terrific American novelist, Joseph Heller, then recently deceased. (Heller died in 1999; Vonnegut followed him into the same hazy country in 2007.)

JOE HELLER

True story, word of honor:

Joseph Heller, an important and funny writer

now dead,

and I were at a party given by a billionaire

on Shelter Island.

I said, “Joe, how does it make you feel

to know that our host only yesterday

may have made more money

than your novel ‘Catch-22’

has earned in its entire history?”

And Joe said, “I’ve got something he can never have.”

And I said, “What on earth could that be, Joe?”

And Joe said, “The knowledge that I’ve got enough.”

Not bad! Way to go, Joe!

Rest in peace!

May your coming days be merry and bright!

Until next time.

Jim

P.S.: Here’s a second story I can’t resist. Not long before his death, Heller, who, by that time in his life had written many novels, was asked if he would do a career-retrospective interview for a leading intellectual magazine. Yes, he said, he would. At one point during the questioning, the journalist, thinking himself clever, and perhaps quietly delighting in what he hoped would be a query which would make his much more famous and talented subject uncomfortable, asked Heller how he felt about the fact that he had never written another novel as good as Catch-22, the book that made him world-famous. “Not so bad,” came the riposte, “No one else has either.”

P.P.S.: I’ve mentioned this before, but I suppose in the present context I should reprise it. In these matters of not participating further in the Dream, Ruskin proved to be as good as his recommendation. As sole inheritor, after his father’s death in 1864, he found himself in possession of a considerable fortune, a cache which, in today’s dollars, would have been something along the order of $40 million. Before the decade was out, he had spent virtually all of it–in donations to charities, for the purchase of property in central London that he refurbished and then offered to the city’s poor at the lowest possible rents, in buying great works of art that he would use for instruction at Oxford and donate, before his own passing, not just to that august institution, but to many other colleges, universities, and museums around the UK. Indeed, so much of John James’ fortune was disbursed, his son was forced, in order to live decently,–and much against his inclinations–to reprint his older books–most of which he thought were flawed by youthful beliefs which he had not examined thoroughly enough. Throughout the rest of his life, he continued this practice of giving away whatever he could manage. The records of this are legion. To take but one instance, when told by a friend that the furniture at his home, Brantwood in the Lake District, was looking pretty threadbare, he replied, “Well, it was furniture that was good enough for my mother and father, and besides there are many who need the money that would needed to buy new versions of it much more than I do.”

So good! And to read this while watching the impeachment hearings…I hope there is, indeed, a remedy for all the vices of the soul. I keep that hope!

As indeed we all should–keep that hope and keep working toward it ourselves…. 🙂

Thanks again Jim for all your hard work and for sharing Ruskin’s insights and poetry with us all. Happy Christmas and new year!

David

Thanks very much, David! I always told my students that the most important thing in life was to find work they loved which did people some real good. I feel blessed that I have had the chance to do that. Happiest of holidays to you and yours too! 🙂 Jim

Interesting post here from my old friend Jim. Mike x

Thank you, Jim. Warm always the cockles of one’s heart, your writings. Seasons’ greetings.

Thanks, Arjun. Much appreciated.